Economic Growth Rates Necessary to Eliminate the Federal Deficit

Can America grow its way out of $29 trillion in debt? Here’s what it would take.

Federal debt held by the public is over $29 trillion dollars, or about 95 percent of GDP. That ratio is the highest since World War II. Without further action, the CBO projects that debt held by the public will climb to 156 percent of GDP by 2055.1

To reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio, Congress could look for ways to lower the deficit or increase GDP growth. Many suggest that the US can simply grow itself out of historically high debt levels. That is, they suggest that boosting the economy’s growth rate will so positively affect the federal budget that Congress won’t have to raise taxes, reform entitlements, or make other politically hard spending decisions.

How much would GDP have to grow to eliminate the deficit without raising taxes or cutting spending? An idea of the necessary targets could help Congress craft legislation to balance the budget.

We provide some back-of-the-envelope estimates of that golden economic growth rate below. We also show the growth required to balance the budget under two different scenarios with cuts to mandatory spending.

Economic Growth Without Spending Cuts

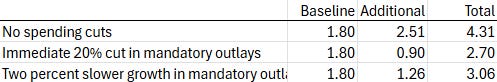

If Congress makes no changes to taxes or spending, we estimate that US real (inflation-adjusted) GDP would need to grow 2.51 percent per year faster than the baseline of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) for each of the 10 years in the current budget window (2026 to 2035) for the annual deficit to fall near to zero by the end of that period (Table 1).

Table 1. Real GDP growth needed to balance the budget in FY2035

Figures are average annual growth rates for 2026-2035 in percentage points. See the attached workbook for our full calculations.

While CBO projects that real GDP growth will settle to 1.8 percent per year, the needed growth would imply an average of 4.31 percent per year. For reference, the US economy has achieved that growth rate in only 32 percent of quarters since 1947.2

With that rate of real growth, debt held by the public falls to 75 percent of GDP by the end of the budget window, compared to rising to 118 percent in the baseline.

An Immediate Cut in Mandatory Spending

Suppose instead that Congress were to reduce mandatory outlays by 20 percent in the first year of the budget window, allowing mandatory outlays to grow from the lower level at the same rate as in baseline. Then real GDP would need to grow an additional 0.90 percent per year to balance the budget at the end of the window.

That puts the annual average at 2.7 percent per year, which is close to the average over the past two years of 2.55 percent.

Such a cut in mandatory outlays would reduce the deficit by $16.5 trillion over 10 years.

Slower Growth in Mandatory Spending

Instead of a sharp cut in the first year, Congress may prefer to phase in the cuts by slowing the growth of mandatory spending. Suppose that the first year of the budget window cuts 2 percent from mandatory outlays in the baseline instead of 20 percent and that mandatory outlays grow 2 percent more slowly than in the baseline in subsequent years.

In that case, real GDP would need to grow 1.26 percent per year faster to balance the budget by the last year. The average annual growth rate would be 3.1 percent per year, a growth rate seen in about half of the quarters since 1947.

By phasing in the cuts, this plan reduces the deficit by only $12.0 trillion over 10 years.

Other Scenarios

At the Fiscal Lab on Capitol Hill, we want to be transparent about how we arrive at our results. We also want to empower congressional staff to experiment on their own.

That’s why we’re publishing a workbook with this report that allows users to reproduce our work and try their own policy scenarios. In the workbook, highlighted cells are modifiable inputs describing faster real growth, an initial cut in mandatory spending, and slower subsequent growth in mandatory outlays. As users modify the inputs, the table for the alternative scenario adjusts automatically.

Details About the Calculation

To find the target growth rate, we increased real GDP growth while using CBO baselines for mandatory or discretionary spending.3

Net interest payments follow the same proportion to debt but shrink with reductions in debt. Total revenues follow the same proportion to GDP as the CBO baseline, so that revenues grow with GDP.

Thus, the increased revenue and decreased interest expense reduce the deficit and slow down the growth in debt. Changes in the deficit for initial years reduce total federal debt in subsequent years.

We also use the CBO baseline price level as measured by the GDP price index.

William Beach is the Executive Director of the Fiscal Lab on Capitol Hill. Parker Sheppard is a Senior Fellow in Economics at the Fiscal Lab on Capitol Hill.

The Long-Term Budget Outlook: 2025 to 2055 (Congressional Budget Office, March 27, 2025), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61187.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Real Gross Domestic Product (GDPC1),” dataset for 1947–2025, accessed September 5, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GDPC1.

The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035 (Congressional Budget Office, January 17, 2025), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/60870.