Weekly Lab Report – October 24, 2025

What the Fiscal Lab Brings to the Table

The federal government shutdown (or more accurately, the slowdown in government activity) continues into its 24th day and is now the second longest in history. The record is the 35-day, 2018–2019 shutdown when Republicans and Democrats sparred over border security. Will this shutdown over ACA subsidies break the record? Time will tell, but there seems little hope of a quick resolution.

However Congress resolves the current impasse, the underlying fiscal challenges remain and continue to worsen. Thus, the sooner Congress gets back to work, the better the chances of real change to improve our fiscal trajectory.

Defining the Terms of Engagement

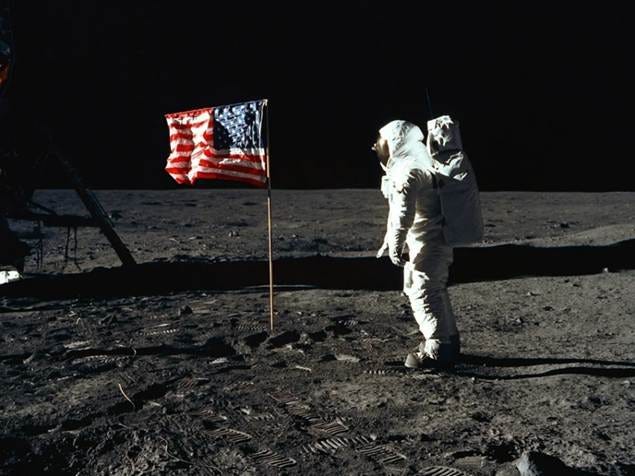

While Members of Congress fiddle, the Fiscal Lab continues to be productive. Doug Branch observes that landing a man on the moon is simpler than solving America’s growing fiscal crisis. Branch describes two main challenges hampering Capitol Hill from addressing our fiscal woes: “a focus on short-form media and rapid news cycles” that distracts from long-term thinking and rapid staff turnover, which causes Congress to have little “institutional knowledge for a functioning budget process.”

Branch explains that no question is too small or too complex for the Fiscal Lab. From “What is GDP?” to “What are the budgetary effects of a piece of legislation in light of demographic and regulatory changes?”, the Fiscal Lab is here to help staffers and their bosses learn.

Back to Basics

Joseph McCormack has a new primer on the difference between deficits and debt. This short overview is the first in a series of primers on basic economic concepts. A deficit is a one-time budget shortfall where outlays exceed revenues. A deficit adds to an overall debt balance. Deficits and debts are not inherently harmful. McCormack reminds us that the American Founding would not have been possible without debt-financing.

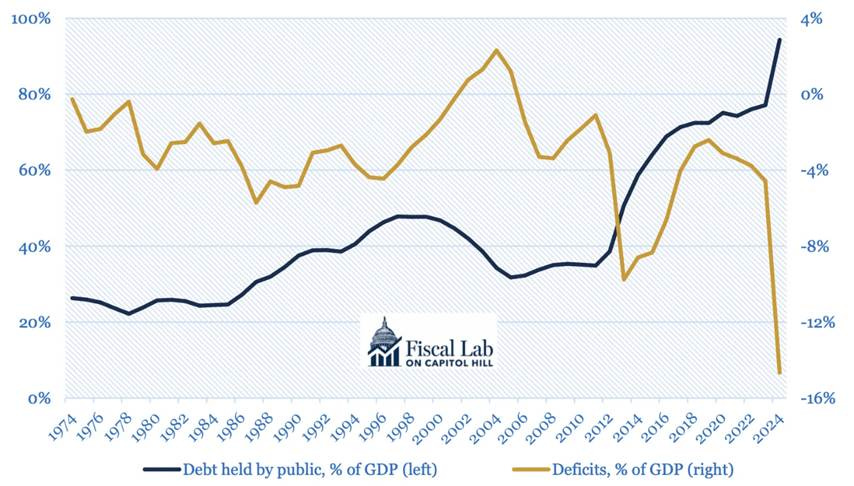

When deficits become chronic and debt becomes difficult to pay off, however, problems arise. The government has less fiscal space to react to emergencies and fund important services. It either must resort to higher future taxes or debt monetization via the creation of new money. McCormack points out that the United States now borrows over 4 percent of its GDP to finance its expenses, while the ratio of debt to GDP has ballooned over the last five decades (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Government Deficits and Debt as a Percentage of GDP

Citation: Federal Debt Held by the Public as Percent of Gross Domestic Product | FRED | St. Louis Fed Federal Surplus or Deficit [-] as Percent of Gross Domestic Product | FRED | St. Louis Fed