Weekly Lab Report – January 7, 2026

Was 2025 an inflection year?

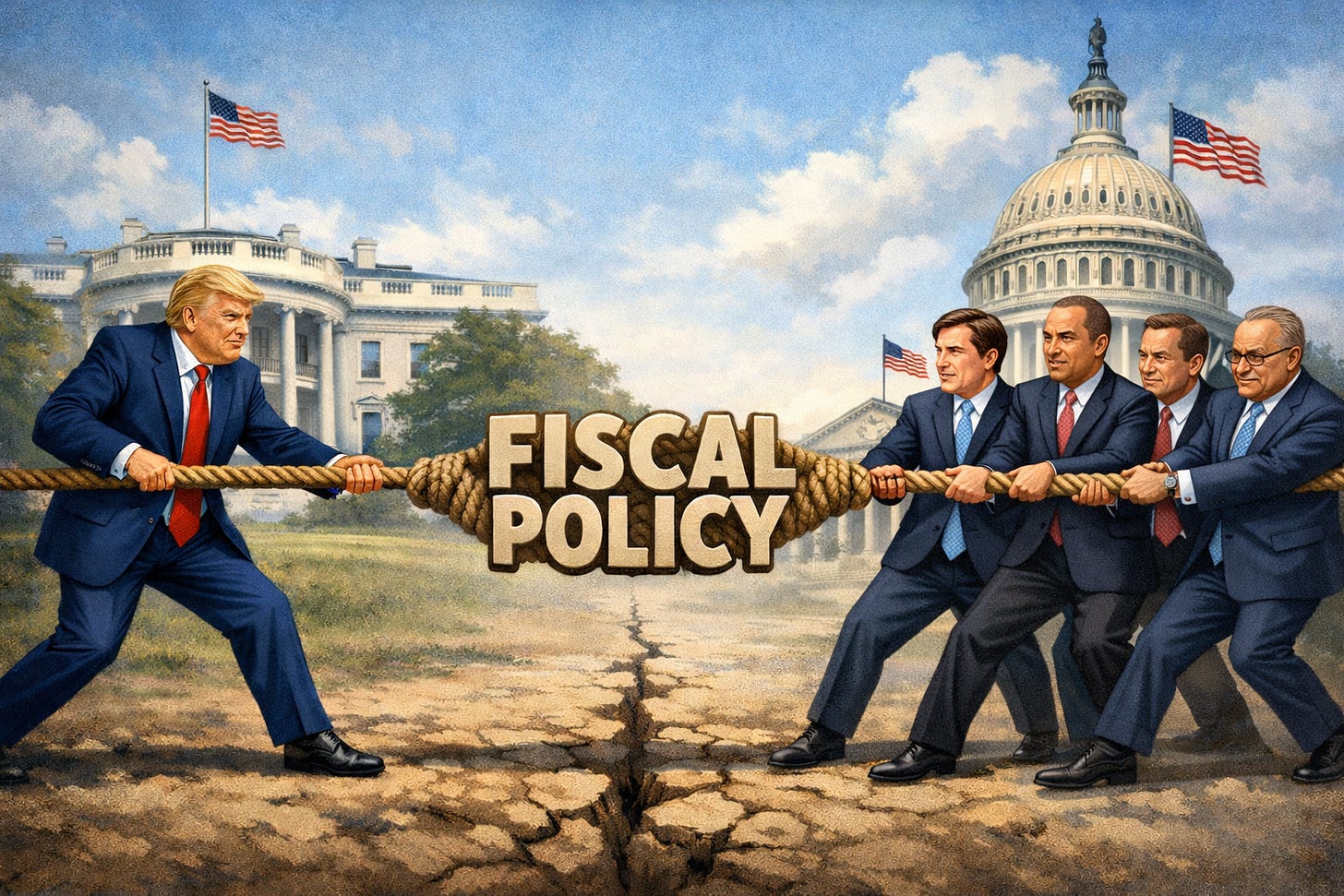

Can one year in federal budgeting and fiscal policy make a difference? We are about to find out.

On surface it seems little in our fiscal situation changed in 2025. Deficits remain large; the national debt is gargantuan and growing. Helping Americans in their daily lives remains a constant theme among all lawmakers: Republicans favor spurring economic growth and individual opportunity through deregulation and tax reductions, evidenced by the One Big Beautiful Bill; Democrats favor expanding and extending entitlements, evidenced by supporting extension (or, now, reauthorization) of ACA Covid-era subsidies. Some things never change, right?

Yet, meaningful steps were taken in 2025 that could change the dynamics of our fiscal situation. First is the question of impoundments: When Congress authorizes and appropriates a sum, is the president bound to spend every dollar? If the president can get a job done for less, or if spending the last bit of a sum has marginal benefits, or is detrimental to the security of the republic, must the president spend? (This is separate from the question of deficiencies, which occur when an administration spends more than what Congress has appropriated.) Washington, Jefferson, and Madison all declined to spend all that was appropriated. The recent phenomena of insisting that all moneys appropriated be spent is a 1970s-era development that the current administration is challenging and that could have a tremendous long-term fiscal effect. Among other things, rescissions could put new pressure on Congress to constrain its spending plans. Rescissions could also send powerful signals to money markets that the federal government is truly serious about reducing deficits.

Another question involves the nature and accountability of the administrative state, and what the current administrations calls “formerly independent” agencies. The alphabet soup of federal independent agencies flowing from the Progressive era has long been constitutionally questionable yet perceived as unchallengeable. Today, the Trump administration is challenging that system, and if the federal judiciary finds merit in their arguments, the actions of so-called independent agencies may finally be held accountable to the American public with potentially major fiscal effects.

A third question involves the functioning of the executive branch departments and agencies in the wake of reductions in force (RIF). Many agencies and programs have been mothballed, and these changes will not be quickly or easily reversed, even if a new administration that is hostile to Trump is elected. Arguably, Trump’s reductions in force have been messy and morale-killing. How many of those RIF’d will be willing to return in the future? That will likely leave countless programs lacking infrastructure and the institutional knowledge to quickly resume operations. Hence, the ability to operate programs and spend money may be slowed beyond the Trump administration, regardless of the 2028 election outcome.

The present administration is challenging much that those of us older budgeteers thought to be true. Congress does have the power of the purse, but the claim feels hollow given the body’s perpetual rubber-stamping of programs that are redundant, counterproductive, or otherwise nonsensical. Much of this has now been upended. Few policymakers will have the audacity to publicly celebrate this, though silently Republicans and Democrats alike should perhaps thank President Trump for clearing out the dead underbrush of federal programs to allow for the growth of new programs better tuned to the needs of today.

With today’s zero-sum game of politics, legislative gridlock seems likely to remain, at least as long as the minority retains some rights in the Senate. I don’t pretend to know the answer, because minority rights are important in the Senate, yet today’s gridlock effectively strips Congress of its power of the purse, giving more leverage to the executive branch. This is the new norm, with Congress passing omnibus or minibus appropriations or continuing resolutions that lack a real exercise of congressional spending power, meaning that programs and spending and interest on debt increases while the nation’s economic output is hobbled, opportunity for all Americans is reduced, and desperately needed fiscal space is crowded out.

Like it or not, some—if not many—of these Trump reforms will survive court challenges, and hence 2025 will likely be recorded as a major adjustment year for federal spending. The question now is whether Congress will be left in the dust. Fortunately for Congress, the launch and opening of the Fiscal Lab offers at least a source of new staff education and fiscal analysis to help members reassert Congress’s control over spending, if they dare. Truly, these are exciting times to be engaged in the federal fiscal space.