Weekly Lab Report – December 17, 2025

Grim Signals in US Labor Markets, CBO Reform, and Book Recommendations

Fiscal Lab Notes is the official Substack page for the Fiscal Lab on Capitol Hill. You can check out all our work and analyses at fiscallab.org.

For our last weekly report of 2025, the Fiscal Lab has new analysis on the state of US labor markets and ways to improve the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). And on a more light-hearted note, we also share staff book recommendations we read this year!

Rejuvenating the CBO

In a new Fiscal Lab brief, Joseph McCormack explains how the CBO can improve its analysis and transparency. McCormack points out that when CBO scores (i.e., quantifies) the budgetary effects of legislation, it primarily uses conventional or static methods. A static score means that potential macroeconomic effects are not considered. For example, a tax cut will lead to less government revenue, all else equal, but the cut might also boost economic growth. The resulting growth may then raise revenue. A static score would not consider the effects of higher growth, but an economic or dynamic score would. Although CBO does provide some economic scoring for major pieces of legislation, McCormack argues this should be the norm for all scores.

McCormack also observes that CBO’s work is insufficiently transparent to allow other economists to double-check its work. He points out that the American Economic Association requires all empirical papers to “provide clear information about the data, programs, and other computational details sufficient to ensure replication.” CBO ought to have the same level of openness. More transparency is not only good for American democracy, but it will also help CBO gain more credibility with Congress.

Alarming Signs in Recent Jobs Data

Writing for the Economic Policy Innovation Center, Fiscal Lab Executive Director Bill Beach analyzes the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ sobering November 2025 jobs report. As Beach points out, the data shows a net increase of 64,000 jobs in November and a net decrease of 105,000 jobs in October. Moreover, the BLS revised August and September jobs numbers downward by 22,000 and 11,000.

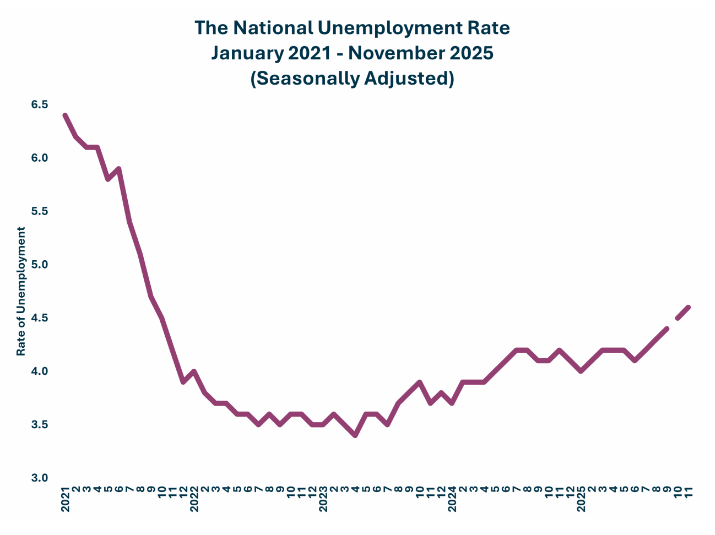

The unemployment rate ticked up to 4.6 percent in November, up from 4.4 percent in September (we will never know the true October unemployment rate because of the lack of survey data due to the government shutdown). The unemployment rate is up a full 0.4 percentage point from November of last year (Figure 1).

Figure 1. National unemployment rate

Source: Economic Policy Innovation Center

With an unemployment rate trending upward and likely more downward revisions to job creation coming, Beach warns “analysts can say without too much disagreement that the trend in labor market activity is decidedly in the wrong direction.”

Recommended Readings

Parker Sheppard

Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider’s View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead (2025) by Kenneth Rogoff. The biggest economic event of 2025 was President Trump’s imposition of tariffs on many US trading partners. The tariffs were meant to address concerns that excess strength from the dollar’s role as a global reserve currency made American exports more expensive and diverted investment from the real economy to financial assets. Rogoff traces how the dollar became the global reserve currency and evaluates the prospects of potential replacements, such as the yuan or Bitcoin. Rogoff argues that the current system contributes to financial instability both at home and abroad, while warning that the current system is not guaranteed to last.

A History of the Bible: The Story of the World’s Most Influential Book (2019) by John Barton. Barton traces the story of the Bible, both the story in the text itself and how that text was received and passed on over time. Just as important as the text is how people have read and interpreted it. He points out that key tenets of both Judaism and Christianity are not found in the text. Barton offers a balanced treatment, providing both critical study of the text and a genuine effort to understand how the text communicates truth. Relevant to the Fiscal Lab, his advice is worth remembering not just for reading the Bible but also for understanding the results of economic models.

Joseph McCormack

The Fifth Risk (2018) by Michael Lewis. Lewis examines what the US federal government does and the risks it manages, often out of public view. He interviews a former Department of Energy chief risk officer, who recounts five major risks the department worried about: lost or mishandled nuclear weapons, North Korea’s nuclear program, Iran-related nuclear risks, failure or attack on the electrical grid, and project-management failure. This “fifth risk” is the slow accumulation of failures leading to systemic weaknesses that can become catastrophic when neglected. Lewis shows the consequences when leadership undervalues staffing and institutional knowledge. He shows how quickly expertise can be lost, how difficult it is to rebuild once gone, and why that fragility matters for national safety and prosperity.

Red Ink: Inside the High Stakes Politics of the Federal Budget (2012) by David Wessel. Red Ink is a fast-paced narrative of how the federal budget actually works. Written in the aftermath of the Great Recession, it captures the deficit-driven fights that continually lead to the fiscal cliff we are facing. Wessel argues that budget debates are both highly consequential and widely misunderstood, in part because so much federal spending runs on autopilot. He explains why healthcare spending growth and rising interest costs dominate the long-run fiscal outlook, and why borrowing has financed a third of federal outlays. Rather than relying on textbook descriptions, he tells the story through the lens of real decision-makers and institutions, including the OMB and the Congressional Budget Office. The book is a clear portrait of how brinkmanship and process constraints can shape outcomes as much as the underlying economics.

Doug Branch

Apollo 13 (2006) by Jim Lovell and Jeffery Kluger. Lovell’s tale, which was faithfully presented in the 1995 blockbuster movie of the same name—but with greater precision in the book—takes the reader to the daring days of America’s early space exploration, reflecting on Lovell’s experience as a test pilot through the final Apollo mission’s successful failure. It’s a story of teamwork, dedication, and problem solving in the highest degree and under the greatest pressure. And it reminds readers of the nation’s dedication to the program, and the national prestige that Apollo inspired. If you liked the movie, you will even more enjoy this work of Lovell, who passed in August of this year.

Who Can Hold the Sea: The US Navy in the Cold War, 1945–1960 (2022) by James D. Hornfischer. Hornfischer’s final work, Who Can Hold the Sea, makes a forceful case for the continued necessity of a strong naval presence in the nuclear age that is increasingly focused on air power and ballistic missiles. This work offers a driving and compelling history from World War II to the atomic tests, the Korean War, nuclear-powered vessels, and the use of naval platforms for launching unimaginably terrible weapons.

From a fiscal policy standpoint, in the background of both space and naval efforts, is the reality that both require dedication of enormous sums of federal taxpayer resources, which the US was, perhaps, better able to absorb before the absolute explosion of mandatory/entitlement spending programs and changing demographics leading to fewer taxpayers supporting a greater number of program beneficiaries as we have today.

Both books are historically illuminating, and they will lead thoughtful readers to reflect on the effects of our limited fiscal space a quarter into the 21st century with debt servicing costs crowding out new opportunities for advancing human knowledge, broad-based and shared economic growth across the economy, and strengthening our nation’s security and ability to serve as a beacon of freedom to the world. The books’ histories are great in themselves, but when contemplated three-dimensionally with the fiscal plane in view, they also beg many questions with respect to 2025 and America’s fiscal choices, if we are to remain the great nation that we have been blessed to inherit.

Patrick Horan

The Monetarists: The Making of the Chicago Monetary Tradition, 1927–1960 (2023) by George Tavlas

Anyone interested in the history of macroeconomic and monetary thought should read this volume. The book chronicles “the Group,” a set of eight University of Chicago economists. Seven of the Group—Paul Douglas, Henry Simons, Frank Knight, Aaron Director, Garfield Cox, Lloyd Mints, and Jacob Viner—were on the Chicago faculty by the 1930s and very active in making proposals for addressing the Great Depression. The eighth member was Milton Friedman, himself, who was a graduate student at Chicago in the early 1930s and returned there as a faculty member in 1946.

Tavlas recounts the Group’s analysis on and clashes over fractional-reserve banking, the velocity of money, monetary policy rules, and flexible exchange rates versus the gold standard. The reader also learns how the progressive Douglas left the university to serve in World War II as a private in the Marine Corps (at age 50!) and how his departure allowed Knight to bring acolytes like Milton Friedman and George Stigler on board and to ensure Chicago’s place as a market-oriented department. The Monetarists is essential reading for those interested in the evolution of the macroeconomics of the Chicago school.

The Fiscal Lab wishes you and yours a merry Christmas and happy holiday season, and we will back with the next Weekly Lab Report in 2026!